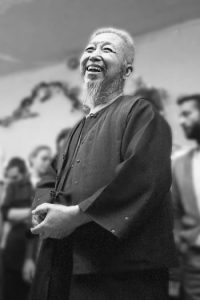

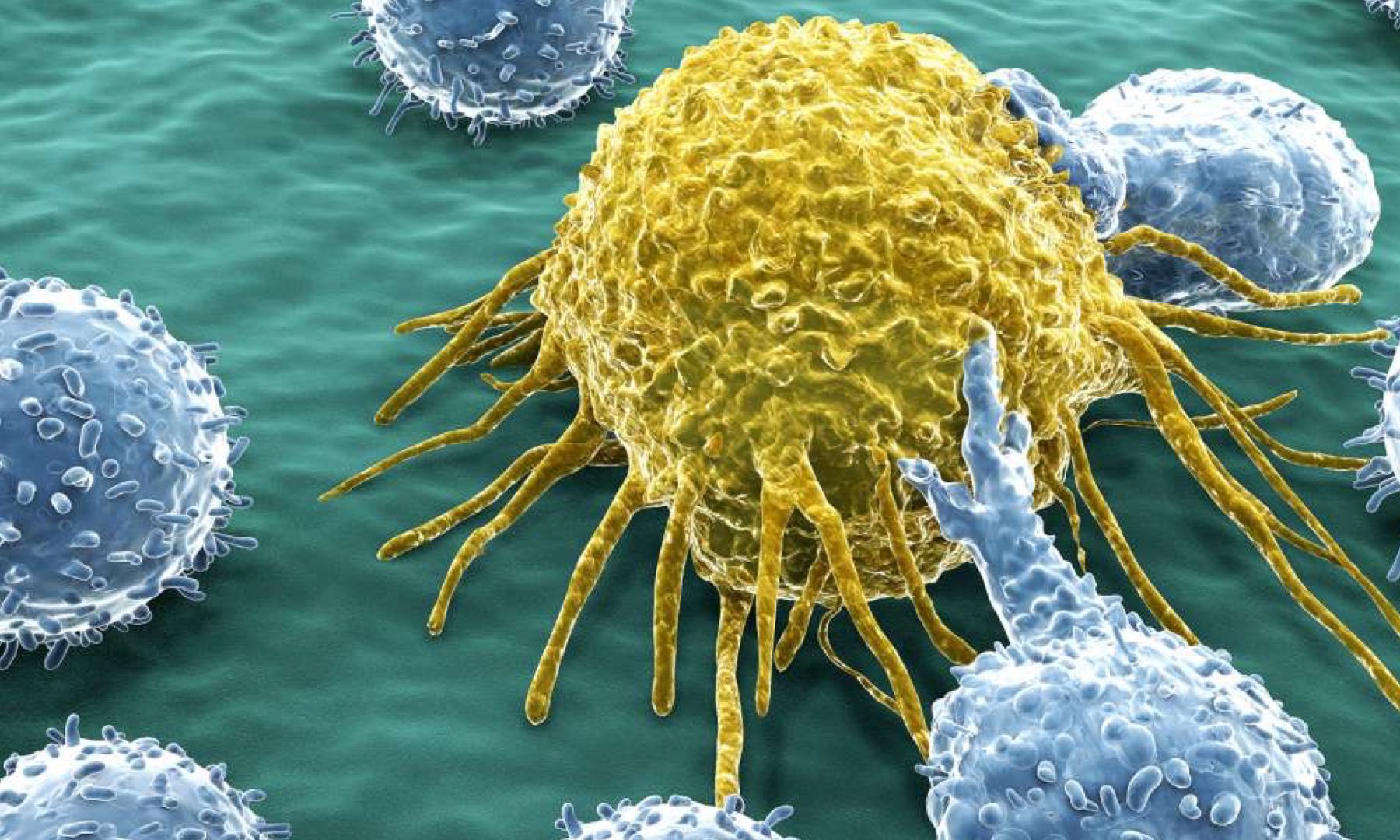

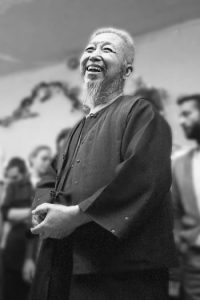

Cheng Man Ching is one of the greats of contemporary Tai Chi and is the single best-known contributor to the spread of Chinese internal arts to the US where today millions of people practice Tai Ji. Professor Cheng as he was referred to as, was also an accomplished doctor who helped hundreds of patients with terminal cancer to cure completely and live long after western doctors had given them the “death sentence”. Below is the introduction to a seminal paper Master Cheng wrote covering the topic of cancer, one of his keenest interests. I share this text with the utmost respect to those that had taken up the challenge of translating the text from original Chinese, and publishing it.

Cheng Man Ching is one of the greats of contemporary Tai Chi and is the single best-known contributor to the spread of Chinese internal arts to the US where today millions of people practice Tai Ji. Professor Cheng as he was referred to as, was also an accomplished doctor who helped hundreds of patients with terminal cancer to cure completely and live long after western doctors had given them the “death sentence”. Below is the introduction to a seminal paper Master Cheng wrote covering the topic of cancer, one of his keenest interests. I share this text with the utmost respect to those that had taken up the challenge of translating the text from original Chinese, and publishing it.

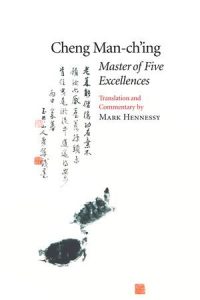

While I understand that the text is copyrighted, I still think that it is of utmost importance to have this invaluable text available to as many people as possible. I have no doubt in my mind that Master Cheng’s intention was that his wisdom would benefit as many people as possible. After studying the topic of cancer nearly two decades I found Master Cheng’s analysis on the topic the single most useful analysis on the topic of cancer, even though just 8 short pages long. For further convenience for the modern reader, I’ve broken the text down to individual posts as the chapters are presented in the original text. I’ve emitted chapter 9 – which covers the topic of surgery – as unfortunately many have already gone through surgery at the time they become interested in such texts. At least that have been my experience so far. I will anyhow say that Master Cheng, as any traditional Chinese internist, does not support surgery, and sees it as one of the primary causes for cancer to spread throughout the body. I will at some point add a commentary on the topic of surgery, and will include Master Cheng’s seminal text as part of it.

My personal connection with Master Cheng is strong, even though I was not blessed to meet with him in person. The first internal martial arts that I learned was Cheng Man Ching style Tai Chi, which is a simplified form with focus on health benefits and general well being. Some years later I had the great fortune of meeting with my Shifu, a legendary martial arts master, and a skilled Chinese doctor, who lacking a better expression, gave me life. He is the chief disciple of Chiao Chang Hung, a titan of the 20th century Internal Martial arts and the founder of Taipei Tai Chi Association. Grandmaster, together with another legend, Chen Pan Ling, started the association in order to support the spread of Chinese internal martial arts throughout the world. Cheng Man Ching became the most successful many masters who took on that task of vital importance. Today, his style of Tai Chi is the most widely practiced form of Chinese internal martial art in the west.

It is with great reverence that I share this one of a kind commentary on the topic that had created more havoc and despair than any other during past 50 years since Master Cheng had originally wrote the commentary.

Part 1 – Introduction

Part 2 – History

Part 3 – Symptoms

Part 4 – Nature and Composition

Part 5 – Causes

Part 6 – From First Sensation to Development and the Mistake of Procrastination

Part 7 – Treatment

Part 8 – [not available]

Part 9 – Prevention

Part 10 – Afterword

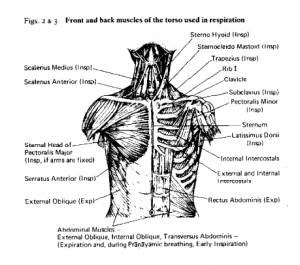

Pranayama (Chinese Qi Gong, Tibetan Cha Lung) is a series of practices focused on the breath. These practices have become increasingly popular over the past decade or two, but unfortunately most people are doing the practices completely wrong. When done right, Pranayama can heal serious illness without any other method complimenting it. Because these practices are so potent, when done wrongly, the same practices can also be the cause of serious illness, or even death.

Pranayama (Chinese Qi Gong, Tibetan Cha Lung) is a series of practices focused on the breath. These practices have become increasingly popular over the past decade or two, but unfortunately most people are doing the practices completely wrong. When done right, Pranayama can heal serious illness without any other method complimenting it. Because these practices are so potent, when done wrongly, the same practices can also be the cause of serious illness, or even death. Cheng Man Ching is one of the greats of contemporary Tai Chi and is the single best-known contributor to the spread of Chinese internal arts to the US where today millions of people practice Tai Ji. Professor Cheng as he was referred to as, was also an accomplished doctor who helped hundreds of patients with terminal cancer to cure completely and live long after western doctors had given them the “death sentence”. Below is the introduction to a seminal paper Master Cheng wrote covering the topic of cancer, one of his keenest interests. I share this text with the utmost respect to those that had taken up the challenge of translating the text from original Chinese, and publishing it.

Cheng Man Ching is one of the greats of contemporary Tai Chi and is the single best-known contributor to the spread of Chinese internal arts to the US where today millions of people practice Tai Ji. Professor Cheng as he was referred to as, was also an accomplished doctor who helped hundreds of patients with terminal cancer to cure completely and live long after western doctors had given them the “death sentence”. Below is the introduction to a seminal paper Master Cheng wrote covering the topic of cancer, one of his keenest interests. I share this text with the utmost respect to those that had taken up the challenge of translating the text from original Chinese, and publishing it.

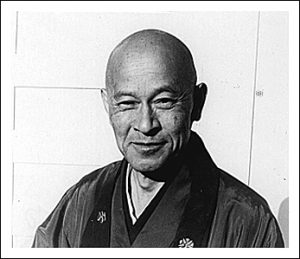

Which is more important: to attain enlightenment, or to attain enlightenment before you attain enlightenment; to make a million dollars, or to enjoy your life in your effort, little by little, even though it is impossible to make that million; to be successful, or to find some meaning in your effort to be successful? If you do not know the answer, you will not even be able to practice zazen; if you do know, you will have found the true treasure of life.

Which is more important: to attain enlightenment, or to attain enlightenment before you attain enlightenment; to make a million dollars, or to enjoy your life in your effort, little by little, even though it is impossible to make that million; to be successful, or to find some meaning in your effort to be successful? If you do not know the answer, you will not even be able to practice zazen; if you do know, you will have found the true treasure of life. In meditation practice, as you sit with a good posture, you pay attention to your breath. When you breathe, you are utterly there, properly there. You go out with the out-breath, your breath dissolves, and then the in-breath happens naturally. Then you go out again. So there is a constant going out with the out-breath. As you breathe out, you dissolve, you diffuse. Then your in-breath occurs naturally; you don’t have to follow it in. You simply come back to your posture, and you are ready for another out breath. Go out and dissolve: tshoo; then come back to your posture; then tshoo, and come back to your posture.

In meditation practice, as you sit with a good posture, you pay attention to your breath. When you breathe, you are utterly there, properly there. You go out with the out-breath, your breath dissolves, and then the in-breath happens naturally. Then you go out again. So there is a constant going out with the out-breath. As you breathe out, you dissolve, you diffuse. Then your in-breath occurs naturally; you don’t have to follow it in. You simply come back to your posture, and you are ready for another out breath. Go out and dissolve: tshoo; then come back to your posture; then tshoo, and come back to your posture.